The weather has been wicked windy

The latest events have made me wonder if Congress on the State and Federal level and or rhetoric from Republicans and folks who lean right of center will really get the push back or beat back by the Democratic Party after Congress gets back from Easter break because i sure have not heard much from the Democratic Party in general and that is not only disturbing it is offensive to anyone who voted these folks into office. I will say it was good to hear that Leader Reid has decided to hold an up and down vote on the PaulRyan Budget. It should open the eyes of most if not all Republican constituents, well maybe. In a time when millions are unemployed, more layoffs coming and Corporate America is still outsourcing and holding jobs hostage. The Republican Party continues to cut slash and burn American Workers. The party of No, which used to be just a conservative pro-life scary group, is now so extreme that the slogan “taking their country back”, is no longer code but an overt statement from Republican Tea Party members. Obviously, it is about not wanting “his kind” in the White House. The Tea Party wants to Privatize Public Service Jobs, which includes Teachers, Fire Fighters, Police, and others while gutting Social Service programs that help the elderly, women, and children around the country suffering already but are now willing to take the basics away from the middle/lower class.

However, I cannot begin to say how offensive though enlightening it is that they are actually legislating people into poverty. I have to say this has made me wonder what our neighborhoods will look after this nasty group is finished wreaking havoc on us all. We all know the more folks that are out of work the better the chances of fewer or quality services will be available. I ask everyone to just think what having less police, firefighters to help out not just the less fortunate but all those above the poverty line … a fire does not care if you have lots of money. I have to say the light of day on how low a Political Party is willing to go was quite evident with those behind the door deals they made to keep SOME firefighters and police employed. Did they think about this?

The media and certain Politicians say that in times of crisis people separate into cliques. I say our Politicians and Talking heads; “the media” have been doing a great job in forcing the public and or viewer into choosing side’s every day depending on the issue. It is offensive and while the November Midterms was proof of how that manipulation works, clearly a whole lot of buyer’s remorse has set in for the Political Party of No, Tea Party carpetbaggers who said one thing and are doing another. We all probably have family or know people who did March for equal rights, felt compelled, added to and a part of that strength in numbers adage we all hear frequently that i consider so important and speaks volumes when a change is near just over the horizon waiting to happen. This feeling of wanting a better way of life is possibly shared by most is spreading all over the world and while a couple of tyrants have seen the light others continue to participate in overt genocide others shutdown access to the World outside. I get the feeling the Republican Tea Party is a lot like those folks in other countries currently doing all they can to either keep control or take anyone down that happens to be in the way by murdering them …right?. In our case, American voters are demanding freedom but the people with the power have gone rogue without thinking about what the full impact on the lives of the many will be or don’t care and have decided to take that risk and try to usurp the rights of Americans whether it’s done legally, by consensus or not.

We are all Freedom Fighters on some level every day.

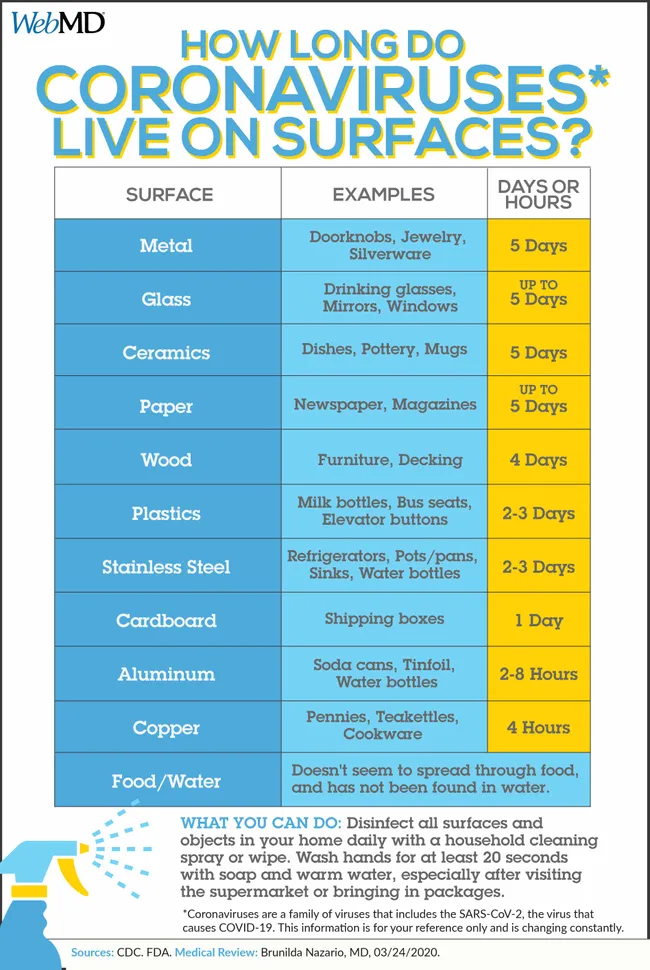

ce suggests that it’s harder to catch the virus from a soft surface (such as fabric) than it is from frequently touched hard surfaces like elevator buttons or door handles,” wrote Lisa Maragakis, MD, senior director of infection prevention at the Johns Hopkins Health System.

ce suggests that it’s harder to catch the virus from a soft surface (such as fabric) than it is from frequently touched hard surfaces like elevator buttons or door handles,” wrote Lisa Maragakis, MD, senior director of infection prevention at the Johns Hopkins Health System.

You must be logged in to post a comment.